Look down at your computer keyboard or phone. Why are the keys arranged in that weird “QWERTY” order? Is it because it is the most efficient layout for typing? Absolutely not. It was designed in the 1870s specifically to slow down typists so the mechanical hammers of old typewriters wouldn’t jam.

So, why do we still use an inefficient 150-year-old design on modern touchscreens?

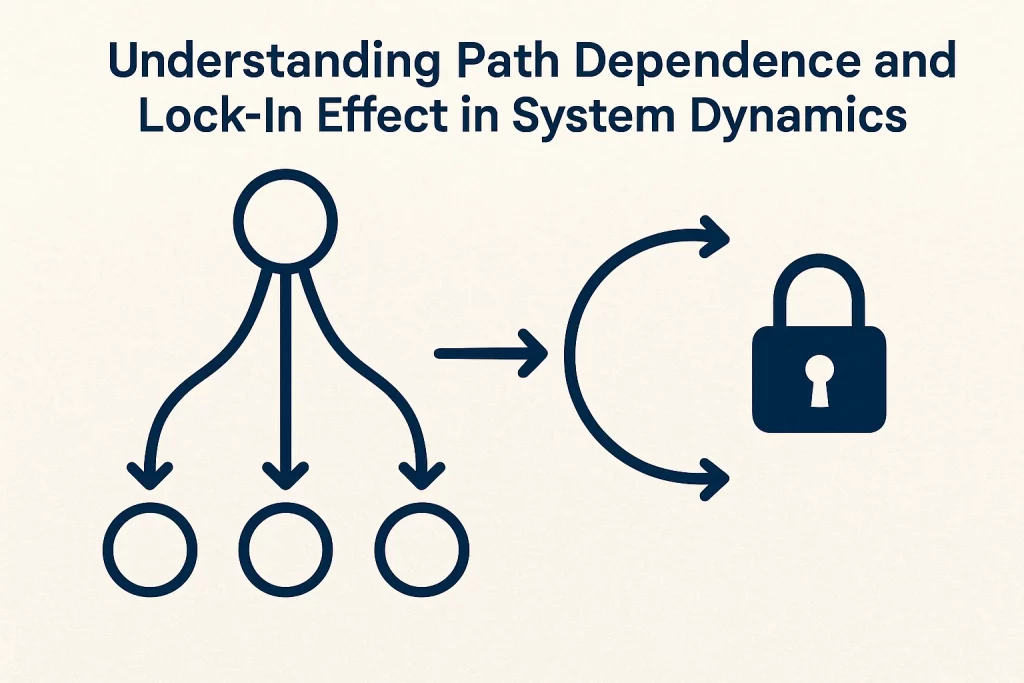

The answer is Path Dependence. In System Dynamics, this concept explains that “history matters.” Where a system ends up doesn’t just depend on where it is now; it depends entirely on the specific path it took to get there. Small, often random events at the beginning of a system’s life can set off a chain reaction that “locks” the system into a specific behavior that is almost impossible to change later.

The Mechanism of Lock-In

In a perfectly rational world, the best technology or the best solution would always win. But in a path-dependent system, the first solution often wins, even if it isn’t the best.

This happens because of Reinforcing Feedback Loops.

1. Early Lead (Sensitivity to Initial Conditions)

At the start of a system, small random events have huge power.

- The QWERTY Example: In the early days of typewriters, the QWERTY layout got a slight head start simply because the Remington company (a major manufacturer) adopted it. It wasn’t better; it was just first.

2. Increasing Returns ( The Snowball)

Once a path is chosen, a Reinforcing Loop kicks in.

- Because Remington sold more typewriters, more typists learned QWERTY.

- Because more typists knew QWERTY, businesses bought more QWERTY machines to match the workers’ skills.

- Because businesses bought QWERTY, schools taught QWERTY.

3. Lock-In

Eventually, the system reaches a point of Lock-In. Even if a vastly superior layout (like Dvorak) is invented, the cost of switching is too high. You would have to retrain every typist and replace every machine. The system is trapped by its own history.

Why “Clean Slates” Don’t Exist

Path dependence destroys the myth of the “clean slate.” In systems thinking, we realize that current decisions are heavily constrained by past decisions.

- Urban Planning: Look at the winding, narrow streets of London or Boston. They follow the paths of cow paths from hundreds of years ago. Once buildings are built along a path (Stock of infrastructure), the path is locked in. You cannot simply “optimize” the city today without destroying the history built on top of it.

- Technology Standards: VHS defeated Betamax not because the picture was better (it wasn’t), but because VHS got a slight early lead in recording time and rental availability. That early lead locked the market into a standard that lasted decades.

The Role of Switching Costs

The invisible force that keeps a system locked into a path is the Switching Cost.

A Systems Thinker asks: “How much energy would it take to jump from the current path to the better path?”

- If the Switching Cost is low, the best solution wins.

- If the Switching Cost is high (like rebuilding a city or retraining a workforce), the old solution wins.

Path Dependence creates a Stock of habit, infrastructure, or learning that acts as a massive weight. To change the path, you don’t just need a better idea; you need an idea so much better that it justifies the massive cost of dumping that accumulated stock.

Conclusion

Path Dependence teaches us humility. It shows us that the “best” solution doesn’t always win. Often, the winner is simply the one that got a lucky head start and built up enough momentum to lock out the competition. For leaders and designers, the lesson is clear: be extremely careful with your early decisions. In the beginning, you have freedom. But as the system grows and the reinforcing loops spin, that freedom vanishes, and history takes the wheel.